The most shocking thing about Banaz’s death is that she had been in the UK with her family for 10 years when her uncle and father decided that she should die for shaming the family. They were Kurdish, originally from Iraq, and one would think that once an oppressed girl-child had reached the UK, had attended high school in London, that she would have reached a place of safety.

Banaz contacted the police 5 times during the years that her husband, a much older man in an arranged marriage, raped and beat her, and during the years afterward when her family had her followed and attempted to kill her twice in order to bring honour back to the family. As shocking, dozens (perhaps more) people in the ex-pat Kurdish community in London knew of the violence coming to Banaz, and did nothing to help her, In fact, they colluded to obstruct the police investigation into her death and protect the murderers. The police themselves are also clearly at fault for not helping her- a video of one of her police interviews is in the film. (See the photo above.) I don’t understand why she wasn’t taken to a shelter that very day.

For me, this film pounded home the truth that although women have reached a country of safety, they may not be safe at all. I recall a student in our ESL school who admitted to me that her father beat her, locked her in her room and took away her cell phone. This was happening in Ottawa, Canada, although he’d been in Canada for many years. She was new to our country and when I informed her of her rights as an adult here, her jaw dropped and she cried. It was hard for her to comprehend the many choices she had to remedy the situation. I put her in counselling with a professional woman from her own culture, in her language (no, not Kurdish).

I thought she was safe- the counselling occurred during class-time once a week. Her father escorted her to and from school, and there was no way she’d have been able to get counselling any other way. In the end, a member of her community, another student in the school, informed her father, and we never saw her again.

There was nothing more I could do. I consoled myself that in the year she’d been with us, her English had improved and she’d been schooled in her options as an abused woman… she had every phone number she needed for the day she was ready to make her move.

Deeyah Khan, the director of Banaz: A Love Story, was careful to include members of the London Kurdish community protesting at the trial of Banaz’s father and uncle who ended up in prison for their crime. The protesters, holding pictures of the 20-year-old, were verbally attacked by the father as he was escorted past them in handcuffs: “You betray the Kurdish community,” he accused them. A courageous woman answers that he is the one without honour.

Banaz was considered by many to have shamed her family by divorcing the man who raped and beat her from the age of 17 when she was forced to marry him. She later fell in love with a man her age and the family learned of this by following her and having her watched by many in the ex-pat community. She kissed this man in a public place. I won’t reveal too many details here as you may decide to view the documentary yourself. (I will say that it starts with an account of her circumcision at the age of 8 in Iraq- no anesthesia or pain killers, just a knife and her father.)

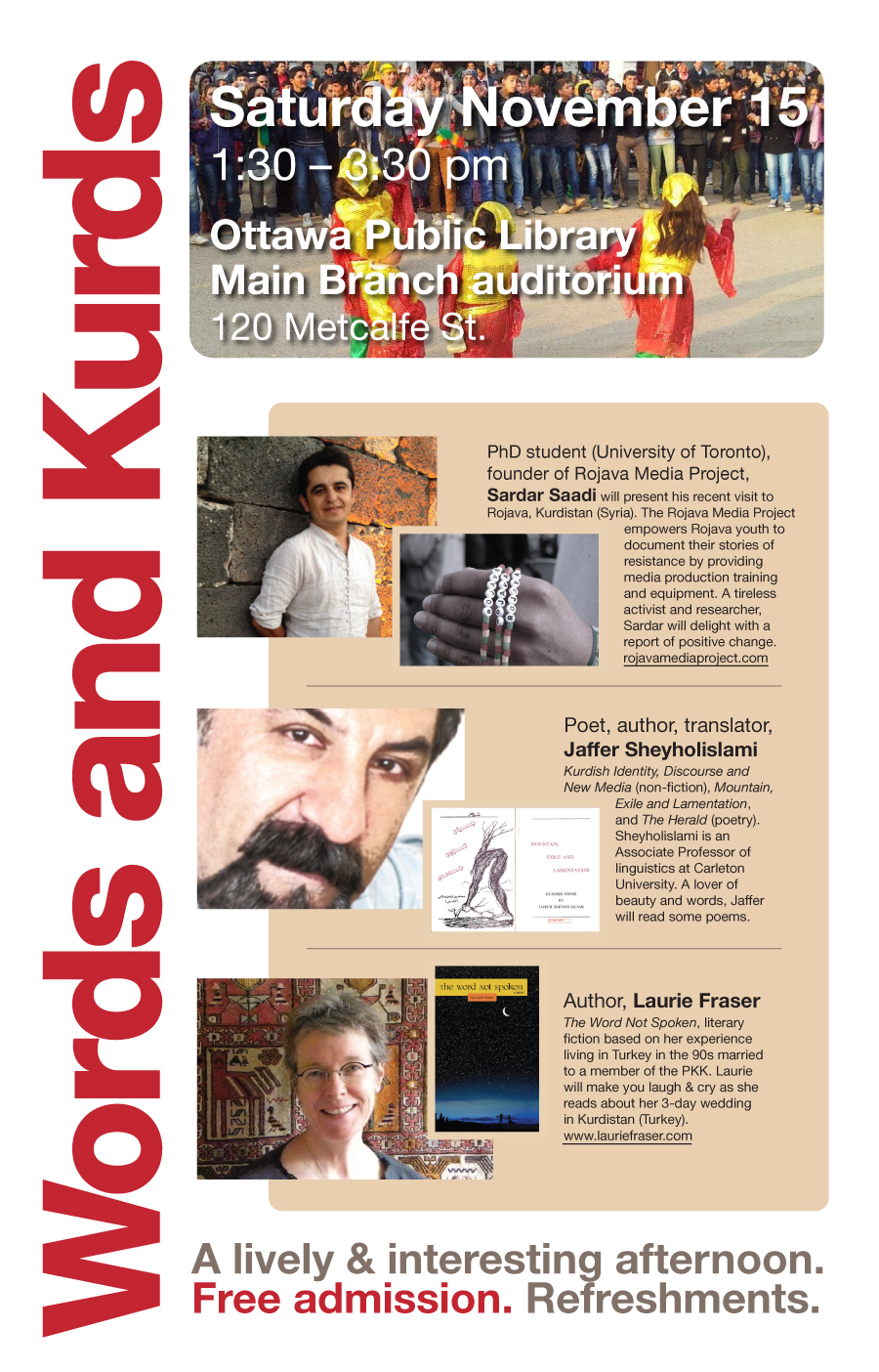

I was told of honour killings when I was in North Kurdistan in 1996- my husband was trying to impress upon me how very traditional the area was in order to get me to modify my behaviour and appearance. The account is in The Word Not Spoken. Leigh has come to Ahmet’s home village to be married. Jess, a South African already married to a Turk, has come along. She is pregnant, but it is Ramadan and no smoking, eating or drinking is allowed during daylight hours.

“What do you want to do?” Leigh asked Jess.

“If we sit here more than half an hour, guests will come, guaranteed,” said Jess.

“I wouldn’t mind if I could understand them.”

“Hey Leigh, maybe I should warn you.” Jess was pawing through her bag, looking for smokes. “Aha!” she pulled out the soft package.

“You can’t smoke!” Leigh braced herself. “Warn me about what?”

“You have to shave everywhere for your wedding night.”

“What do you mean, ‘everywhere’?”

“Men and women shave their underarms and their pubes on their wedding day. It’s a rite of passage for virgins,” said Jess, taking out a sigara and running it through her fingers.

Leigh tightened her mouth and considered this news.

“I really want a sigara. I don’t have to fast because I’m pregnant, but I shouldn’t smoke for the same reason. A quandary.” Jess paused and looked around. “The answer is to hide and smoke.”

The rain had slowed. They decided to go for a walk to find a corner somewhere. The two women slipped out the front door and turned toward the main street. The village was indeed tiny and remote; it had been only five years since the electrical and phone lines had arrived.

The main street, lined with flat-roofed buildings, was mud. Smaller streets branched off it haphazardly. Leigh and Jess headed down one of these, but it seemed to lead out into an open field—nowhere, to Leigh’s way of thinking. They walked back and across an empty village square. Leigh wondered if a pazaar came there once a week. Somehow she doubted it. Life looked simple. Many people had a garden in their yard. Ahmet had told her that most families had farm land in the area and travelled out by horse and wagon to work on it, but today, few people were working in the rain. A couple of children ran through puddles on the mud street.

A few people waited at the door of a small bakery for the unleavened bread to be ready. No baguettes here. Two old men in line shared a broken but functioning umbrella. Their shoes sunk into the mud, and they seemed stuck there, waiting silently for the next batch. When the steaming bread came to the window, there was sudden activity. The old men were served first, and they shuffled away.

A young boy triumphantly drove by on a bike. He steered with one hand and held bread wrapped in newspaper out with the other. The rain plopped loudly on the newspaper as he peddled by, and Leigh caught a warm whiff.

Chickens wandered in and out of yards and roosters crowed. Women were nowhere in sight, but men shadowed the doorways and street corners. Without exception, they wore takkes, white religious skullcaps. The men returned the women’s stares.

“I don’t think they see tourists here,” remarked Jess.

Leigh felt the men’s stares and shivered. “Don’t they look lost without their sigaras and tea?”

The main street was lined with dark men in baggy clothes. Many wore traditional Kurdish pants, the crotch hanging to their knees. A wide band of material was wrapped at the waist. Mud clung to pant hems.

Some men sat at tables in front of the teahouse; others stood in the street and stared. More men came to see what had quieted the others. No one pretended to be doing anything but staring at the white women: a tall blonde, the other with long loose hair.

“Kunda,” said one man.

The women smiled politely and increased their pace. A few children were following them. Every eye in the street watched their progress.

“I don’t think we’re going to get away with a sigara,” Jess deadpanned.

“The baby is happy about it anyway,” said Leigh.

They headed back to the little house, having seen almost every edgeless brown building in the village on their twenty-minute walk. As they approached, Ahmet rushed out to meet them.

“Where have you been? Everyone is worried about you!”

“Really? Where do they think we’re going to go?” asked Jess.

“Jess needs a sigara,” said Leigh.

“You can’t break the fast here, front everyone,” said Ahmet.

“Where can I go then?” asked Jess.

“Here.” He gave her the car keys. “You and Ismail go for a ride.”

“Good idea.” She was immediately cheered and went to find Ismail.

“Ahmet,” asked Leigh, “how do people know which chickens belong to them, when the chickens wander all over the streets like this?”

He laughed. “The chickens know.”

“Oh…the chickens know. What’s kunda?”

His eyes opened very wide. “Where did you hear that word?”

“On the street. A man said ‘kunda’ to me.”

Ahmet shook his head, perturbed. “It means prostitute.”

“No!”

He frowned. “I don’t want you to walk alone on the street again.”

“But I was with Jess. What could happen?”

“My Angel. Nothing will happen. But they see a woman who is uncovered, and they think you are a prostitute. Good women cover. That’s what they believe. You can’t change it.” He took a breath, “Will you cover while you’re here?”

“But I’m not Muslim!” Jess said her refusal to wear a headscarf was a fight against becoming invisible.

“Leigh, it is very hard for people here to understand. They don’t see Western ways like they do in Istanbul. They spend their whole lives here, and they are proud of the old ways.”

“But I can’t change myself for them. They will learn from me that some people are different. A good Muslim will not think ill of me if I am Christian. It says in the Quran they must accept all the children of Abraham.” Leigh was tired and her mouth was dry.

“Gel.” (Come.) He brought her into the house. They settled by the heater on orange and yellow striped cushions. “Listen me. It is difficult for people in Nevsehir to accept Jess, and she has lived there one year. You will be here only a few days. What will you teach them? My family is here all the time, and you must not shame them. Do you understand?”

“Sort of.” Leigh avoided his eyes.

“Would you walk down the streets of London with no clothes?” asked Ahmet.

“Of course not.”

“Why not?”

“That’s a ridiculous question. It’s against the law first of all.”

“It’s against Islamic law to reveal your legs, arms and hair.”

“But Turkey doesn’t have Islamic law.”

“We are very close to the borders of Iran and Iraq here. The law does not matter. The only important thing is what people believe. You know what Kurds think of the government and polis.”

“Yes, many people in Turkey like to take the law into their own hands, you included.” She was referring to his ex-partners. She traced the cushion stripes with her finger: orange then yellow. The fabric was thick as a kilim.

Ahmet raised a finger. “In this village, last year, a teenage girl had sex. She was not married. Our tradition is Islam. She must be killed by a man in her family to give the family honour again.”

“That’s awful!”

“Her brother sat her in a chair, and he sat in a chair across from her. Then he shot her in the heart.”

“Oh my God!” The bit of pink in Leigh’s cheeks faded. “Did she know what he was doing? Why?”

“Of course! He must do it to her face. There are a few of these murders in Kurdistan every year.” He had her full attention.

“But they are subject to Turkey’s laws!”

“Hah. The brother went to jail for seventeen years. He was sacrificed on the family honour.”

“Brother and sister were sacrificed.” She swallowed and wanted water.

“And most people here believe it was right thing.” Ahmet clasped and unclasped his hands, missing his sigara. Leigh watched his hands.

Hey- and I’m not being sarcastic- happy International Women’s Day.

Watch the documentary about Banaz here: https://topdocumentaryfilms.com/banaz-love-story/